for Walpole members and

non-members available now

at The Londoner

A very long time ago, roughly 40 years back, I was employed to compile a list of companies selling luxury product in London. I have no memory of what it was for – I don’t think I was even sure of the purpose at the time – but I do know that I was paid enough to buy a very nice skirt from the Kenzo store on Brook Street. I also know that nobody mentioned the word ‘brand’. But my list was of brands, of course: Floris, Rolls-Royce, Wedgwood, Waterford, Peter Reed, N Peal – a few off the top of my head that I remember. It’s just that back then nobody considered brands in the same way. The retail world was so much smaller in terms of markets and competition and the demands of growth, reinvention and narrative so much less pressing. Branding as a driver of business was still in its infancy – if not embryonic.

Over the past 30 years, though, branding has in some ways become the story. Even the smallest companies think in terms of their brand identity. I brand, therefore I am. The need to create a brand core from which you can evolve is one of the first stages in the invention of any business. And with the shift to e-commerce and digital operations, strong branding is essential. As customers surf the vast oceans of merchandise it is the brands they know, trust and are interested in that they will spot first.

But for brands as with anything the quandary is how to stay alive. How to remain relevant as your customer base ages? How to keep being the story and not relegated to the dull, safe haven of predictability or, worse, become old news?

In fashion, the arena where I have worked for the past 30 years, this is managed with hugely varying degrees of success, but one thing remains constant. The key is in the connection between the creative and business teams. Success relies on a real understanding between the two parts, encompassing genuine trust and shared objectives. Failure tends to follow when companies dive into a copycat response to what may have worked wonders in one business but is not necessarily the right template for another.

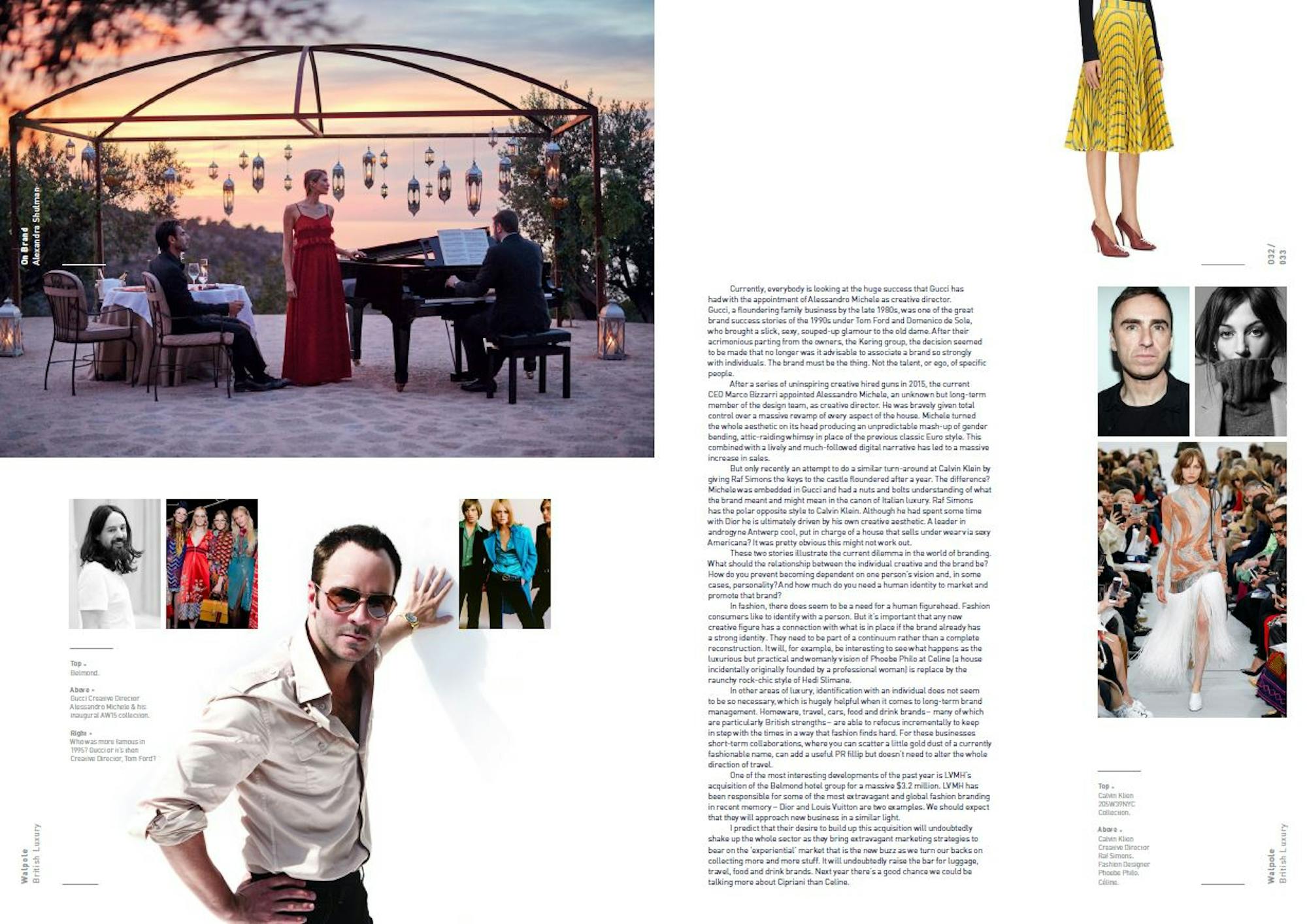

Currently, everybody is looking at the huge success that Gucci has had with the appointment of Alessandro Michele as creative director. Gucci, a floundering family business by the late 1980s, was one of the great brand success stories of the 1990s under Tom Ford and Domenico de Sole, who brought a slick, sexy, souped-up glamour to the old dame. After their acrimonious parting from the owners, the Kering group, the decision seemed to be made that no longer was it advisable to associate a brand so strongly with individuals. The brand must be the thing. Not the talent, or ego, of specific people.

After a series of uninspiring creative hired guns in 2015, the current CEO Marco Bizzarri appointed Alessandro Michele, an unknown but long-term member of the design team, as creative director. He was bravely given total control over a massive revamp of every aspect of the house. Michele turned the whole aesthetic on its head producing an unpredictable mash-up of gender bending, attic-raiding whimsy in place of the previous classic Euro style. This combined with a lively and much-followed digital narrative has led to a massive increase in sales.

But only recently an attempt to do a similar turn-around at Calvin Klein by giving Raf Simons the keys to the castle floundered after a year. The difference? Michele was embedded in Gucci and had a nuts and bolts understanding of what the brand meant and might mean in the canon of Italian luxury. Raf Simons has the polar opposite style to Calvin Klein. Although he had spent some time with Dior he is ultimately driven by his own creative aesthetic. A leader in androgyne Antwerp cool, put in charge of a house that sells under wear via sexy Americana? It was pretty obvious this might not work out.

These two stories illustrate the current dilemma in the world of branding. What should the relationship between the individual creative and the brand be? How do you prevent becoming dependent on one person’s vision and, in some cases, personality? And how much do you need a human identity to market and promote that brand?

In fashion, there does seem to be a need for a human figurehead. Fashion consumers like to identify with a person. But it’s important that any new creative figure has a connection with what is in place if the brand already has a strong identity. They need to be part of a continuum rather than a complete reconstruction. It will, for example, be interesting to see what happens as the luxurious but practical and womanly vision of Phoebe Philo at Celine (a house incidentally originally founded by a professional woman) is replaced by the raunchy rock-chic style of Hedi Slimane.

In other areas of luxury, identification with an individual does not seem to be so necessary, which is hugely helpful when it comes to long-term brand management. Homeware, travel, cars, food and drink brands – many of which are particularly British strengths – are able to refocus incrementally to keep in step with the times in a way that fashion finds hard. For these businesses short-term collaborations, where you can scatter a little gold dust of a currently fashionable name, can add a useful PR fillip but doesn’t need to alter the whole direction of travel.

One of the most interesting developments of the past year is LVMH’s acquisition of the Belmond hotel group for a massive $3.2 billion. LVMH has been responsible for some of the most extravagant and global fashion branding in recent memory – Dior and Louis Vuitton are two examples. We should expect that they will approach new business in a similar light.

I predict that their desire to build up this acquisition will undoubtedly shake up the whole sector as they bring extravagant marketing strategies to bear on the ‘experiential’ market that is the new buzz as we turn our backs on collecting more and more stuff. It will undoubtedly raise the bar for luggage, travel, food and drink brands. Next year there’s a good chance we could be talking more about Cipriani than Celine.

We are now taking bookings for the 2020 Book of British Luxury, please click here to find out more or please contact Stephanie Robinson.