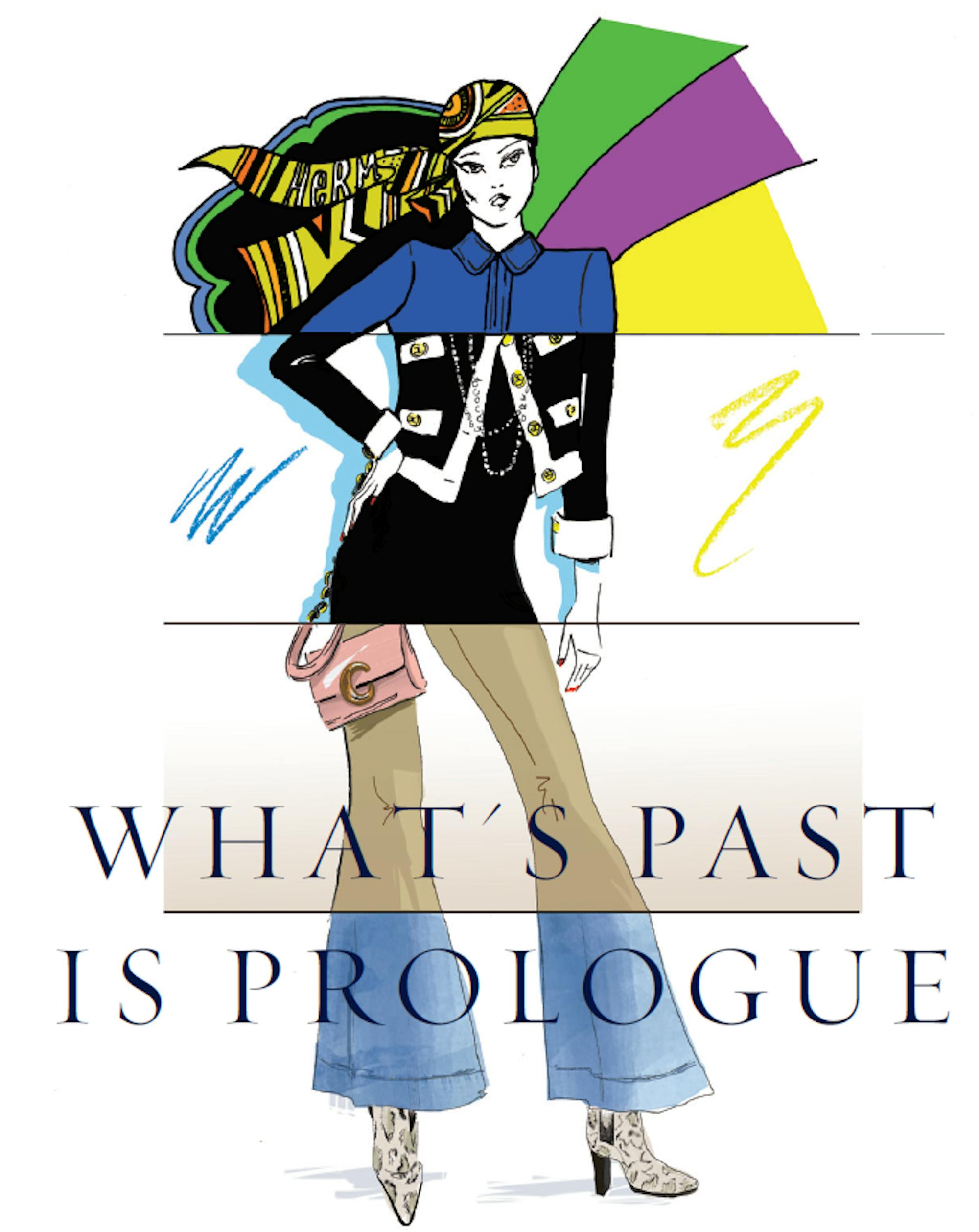

Illustration by Jo Bird.

Shakespeare’s dictum came back to me vividly as I watched my 13-year-old daughter unwrap her much lobbied-for Christmas present: a pair of flared jeans. At her age, I would have recoiled in horror, for my friends and I sneeringly derided the 1970s as “the decade that style forgot”. But the wheel of fashion turns inexorably, and now oversized sunglasses, macrame bags and swishy trousers have conquered the catwalks. Indeed, almost unbelievably, coming over the horizon are the shoulder pads of my own teenage years, which I had believed to be eternally consigned to the sartorial dressing-up box.

If fashion, with its hunger for novelty, continually looks to the past for future inspiration, it is no wonder that great luxury houses do the same, emphasising their legacy to boost consumer perception of their authenticity and depth. But is the strategy itself backward-looking, in our age of constant innovation, fossilising a company in tradition as if in amber?

For Richard Village, of the consultancy Smith & Village, looking back is an essential part of the process of innovation. “We are completely guided by a legacy brand’s archive,” he says. “What resonates with the luxury customer is the concept of decades of expertise, but it can also be helpful in terms of choosing a future direction. When we were asked to look at Harvey Nichols’ food hall in 2017, we first analysed what had made it a success in 1994.” Then, black and white photography and chic metal tins had turned food items into fashion statements, but fashion has moved on since. Instead, Smith & Village transformed the HN monogram into a pattern, and reinvented biscuit tins to resemble lipsticks – with a similarly galvanising effect on sales. “The question is how do you turn hundreds of years of history into something relevant for the coming season?” says Village. “Labels such as Hermès do it impeccably, by producing those iconic scarves in collaboration with designers of the moment. Products have to drive trends as well as being timeless, otherwise you’re just waiting for fashions to come around again.”

I realised the truth of this for myself during the 150th anniversary celebrations of Harper’s Bazaar two years ago. In celebration of this impressive legacy, we rifled our archive to highlight the great editors, writers and artists who contributed to the magazine.

Rather than smiling at anachronisms, I found myself astonished by how avant-garde a publication it had always been. Bazaar’s very first editor-in-chief, Mary Louise Booth, was a prodigious polymath: a prolific author and translator, who recruited writers including Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins as contributors. But she was also a political radical – an anti-slavery campaigner, a feminist who promoted America’s first college for women doctors, and whose friends included Harriet Beecher Stowe, Louisa May Alcott and Abraham Lincoln…

Later editors were radical in different ways. In the 1930s, the great Carmel Snow – who lived up to her own motto that “elegance is good taste, plus a dash of daring” – ushered in an era of unparalleled visual dynamism, hiring Richard Avedon, recruiting Diana Vreeland as her fashion editor after spotting her dancing at a party, and commissioning the first-ever fashion shoot to feature a model in motion.

Far from feeling paralysed by the weight of Bazaar’s extraordinary history, it was liberating to realise the extent to which the magazine had always broken new ground politically, visually and intellectually, in order to appeal to the “well-dressed woman with the well-dressed mind”. The brand DNA did not lie in a particular aesthetic, I realised, but in a willingness to innovate, to experiment and to take risks – a revelation that has proved liberating when I make my own choices about our direction in the 2020s.

But it is the same with all great luxury names that have stood the test of time: at the time they were founded, they fulfilled a need as well as a desire, and their products were not just exquisitely made, but fresh and exciting. From Louis Vuitton’s elegant yet practical invention of a flat-sided and easily stackable trunk, to Cartier’s wristwatch inspired by the blunt lines of a WWI tank, or Coco Chanel’s transformation of mourning attire into ineffably chic eveningwear, timeless pieces always start life as new ideas.

What’s past is prologue, indeed – yet we should remember how Shakespeare continued: “what to come, in yours and my discharge.” Or, to misquote the philosopher George Santayana, those who cannot remember the past may be condemned not to repeat it.